ETIOLOGIA E FISIOPATOLOGIA – FRATURA PATOLÓGICA

As lesões ósseas podem ser osteolíticas, osteoblásticas ou mistas a depender do mecanismo primário que interfere no remodelamento ósseo normal (3). A fratura patológica é muito mais comum nas lesões osteolíticas. A fisiopatologia dessas lesões não está ainda bem definida, mas diferentes vias já foram identificadas no desenvolvimento das lesões metastáticas.

O metabolismo ósseo normal baseia-se em um equilíbrio dinâmico entre formação (ação do osteoblasto) e reabsorção óssea (ação do osteoclasto). Quando as células tumorais atingem a medula óssea, elas interagem com os osteoblastos e osteoclastos levando a um desequilíbrio que gera destruição óssea e simultaneamente liberação de diferentes fatores de crescimento e moléculas adesivas (proteína inflamatória 1a, interleucinas 6 e 3) que permitem que o tumor continue se desenvolvendo (8.9).

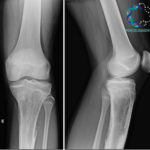

Lesões osteolíticas em fêmur direito secundárias a câncer de mama.

LESÕES OSTEOLÍTICAS

Um dos mecanismos que explica esse ciclo vicioso é a ativação dos osteoblastos pelas células tumorais que, por sua vez, estimulam a produção do receptor ativador do fator nuclear kappa B (RANK) que interage com o seu ligante (RANKL) presente na membrana dos osteoclastos. Uma vez ativados, os osteoclastos reabsorvem o osso de forma exacerbada, causando a metástase osteolítica (8). A osteoprotegerina é uma molécula que inibe a ligação RANK-RANKL ao se ligar ao RANKL, porém ela geralmente está inibida ou diminuída nos pacientes metastáticos e com mieloma múltiplo (9,10). Além disso, muitas vezes o osso normal produz um componente osteoblástico reativo a esse processo, caracterizando as lesões mistas.

Fonte: UptoDate – Mechanisms of bone metastases

Além do RANKL diferentes fatores estimulam a atividade dos osteoclastos, tais como: interleucina 1 e 6 (IL-1 e IL-6), proteína inflamatória 1a, fator de transformação do crescimento beta (TGF-b), proteína relacionada ao hormônio da paratireóide (PTH rP), fator de crescimento de fibroblastos 1 e 2 (FGF-1 e FGF-2), antigeno prostatico especifico (PSA), fator de crescimento derivado de plaquetas (PDGF) e outros.

LESÕES OSTEOBLÁSTICAS

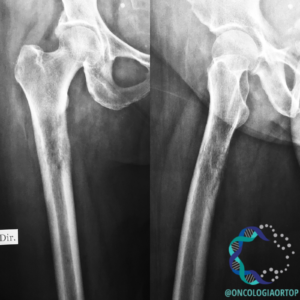

Lesões osteoblásticas em fêmur esquerdo secundárias a câncer de próstata.

As metástases osteoblásticas não tem seu mecanismo bem definido, mas acredita-se que em pacientes com câncer de próstata, por exemplo, algumas moléculas como a endotelina 1, proteínas morfogenéticas ósseas e fatores derivados de plaquetas são responsáveis pela disfunção dos osteoblastos e, consequentemente, pela formação óssea exagerada (11).

A doença óssea destrói a medula óssea e quando passa a afetar também a cortical óssea, aumenta significativamente o risco de uma fratura patológica. As lesões osteolíticas, osteoblásticas e mistas se refletem nas radiografias e a progressão da doença fica mais clara na avaliação radiográfica de cada caso.

Referências:

- Coleman, Robert E. “Clinical features of metastatic bone disease and risk of skeletal morbidity.” Clinical cancer research 12.20 (2006): 6243s-6249s.

- Melton, L. Joseph, et al. “Fracture Risk With Multiple Myeloma: A Population‐Based Study.” Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 20.3 (2005): 487-493.

- Saad, Fred, et al. “Pathologic fractures correlate with reduced survival in patients with malignant bone disease.” Cancer 110.8 (2007): 1860-1867.

- Piccioli, Andrea, et al. “Bone metastases of unknown origin: epidemiology and principles of management.” Journal of Orthopaedics and Traumatology 16.2 (2015): 81-86.

- Sim, F. H. “Metastatic bone disease of the pelvis and femur.” Instructional course lectures 41 (1992): 317-327.

- Yong-cheng, H. U., L. U. N. Deng-xing, and W. A. N. G. Han. “Clinical features of neoplastic pathological fracture in long bones.” 中华医学杂志 (英文版) 2012 年 17 (2012): 3127-3132.

- Selvaggi, Giovanni, and Giorgio V. Scagliotti. “Management of bone metastases in cancer: a review.” Critical reviews in oncology/hematology 56.3 (2005): 365-378.

- Body, Jean-Jacques, et al. “A study of the biological receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand inhibitor, denosumab, in patients with multiple myeloma or bone metastases from breast cancer.” Clinical cancer research 12.4 (2006): 1221-1228.

- Sezer, Orhan, et al. “Immunocytochemistry reveals RANKL expression of myeloma cells.” Blood 99.12 (2002): 4646-4647.

- Lacey, D. L., et al. “Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation.” cell 93.2 (1998): 165-176.

- Yin, Juan Juan, et al. “A causal role for endothelin-1 in the pathogenesis of osteoblastic bone metastases.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100.19 (2003): 10954-10959.

- Fayad, Laura M., et al. “Distinguishing stress fractures from pathologic fractures: a multimodality approach.” Skeletal radiology 34.5 (2005): 245-259.

- Bickels, Jacob, Shlomo Dadia, and Zvi Lidar. “Surgical management of metastatic bone disease.” JBJS 91.6 (2009): 1503-1516.

- Nazarian, Ara, et al. “Treatment planning and fracture prediction in patients with skeletal metastasis with CT-based rigidity analysis.” Clinical Cancer Research (2015).

- Harvey, Harold A., and Leah von Reyn Cream. “Biology of bone metastases: causes and consequences.” Clinical breast cancer 7 (2007): S7-S13.

- Behnke, Nicole K., et al. “Risk factors for same-admission mortality after pathologic fracture secondary to metastatic cancer.” Supportive Care in Cancer 25.2 (2017): 513-521.

- Pockett, R. D., et al. “The hospital burden of disease associated with bone metastases and skeletal‐related events in patients with breast cancer, lung cancer, or prostate cancer in Spain.” European journal of cancer care 19.6 (2010): 755-760.

- Mirels, Hilton. “Metastatic Disease in Long Bones A Proposed Scoring System for Diagnosing Impending Pathologic Fractures.” Clinical orthopaedics and related research 249 (1989): 256-264.

- Mirels, Hilton. “The Classic: Metastatic Disease in Long Bones A Proposed Scoring System for Diagnosing Impending Pathologic Fractures.” Clinical orthopaedics and related research 415 (2003): S4-S13.

- Damron, Timothy A., et al. “CT-based structural rigidity analysis is more accurate than Mirels scoring for fracture prediction in metastatic femoral lesions.” Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® 474.3 (2016): 643-651.

- Soldatos, Theodoros, et al. “Imaging differentiation of pathologic fractures caused by primary and secondary bone tumors.” European journal of radiology 82.1 (2013): e36-e42.

- Fayad, Laura M., et al. “Distinction of long bone stress fractures from pathologic fractures on cross-sectional imaging: how successful are we?.” American Journal of Roentgenology 185.4 (2005): 915-924.

- Kao, Chia-Hung, et al. “Comparison and discrepancy of 18F-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography and Tc-99m MDP bone scan to detect bone metastases.” Anticancer research 20.3B (1999): 2189-2192.

- Jacofsky, David J., and George J. Haidukewych. “Management of pathologic fractures of the proximal femur: state of the art.” Journal of orthopaedic trauma 18.7 (2004): 459-469.

- Datir, Abhijit, Pierre Pechon, and Asif Saifuddin. “Imaging-guided percutaneous biopsy of pathologic fractures: a retrospective analysis of 129 cases.” American Journal of Roentgenology 193.2 (2009): 504-508.

- Saarto, Tiina, et al. “Palliative radiotherapy in the treatment of skeletal metastases.” European Journal of Pain 6.5 (2002): 323-330.

- Sarahrudi, Kambiz, et al. “Surgical treatment of metastatic fractures of the femur: a retrospective analysis of 142 patients.” Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 66.4 (2009): 1158-1163.

- Zore, Zvonimir, et al. “Surgical treatment of pathologic fractures in patients with metastatic tumors.” Collegium antropologicum 33.4 (2009): 1383-1386.

- Steensma, Matthew, et al. “Endoprosthetic treatment is more durable for pathologic proximal femur fractures.” Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® 470.3 (2012): 920-926.

- Gainor, Barry J., and Peter Buchert. “Fracture healing in metastatic bone disease.” Clinical orthopaedics and related research 178 (1983): 297-302.

- Dijkstra, Sander, et al. “Treatment of pathological fractures of the humeral shaft due to bone metastases: a comparison of intramedullary locking nail and plate osteosynthesis with adjunctive bone cement.” European Journal of Surgical Oncology (EJSO) 22.6 (1996): 621-626.

- Yazawa, Yasuo, et al. “Metastatic Bone Disease: A Study of the Surgical Treatment of 166 Pathologic Humeral and Femoral Fractures.” Clinical orthopaedics and related research 251 (1990): 213-219.

- Bouma, W. H., and M. Cech. “The surgical treatment of pathologic and impending pathologic fractures of the long bones.” Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 20.12 (1980): 1043-1045.

- Wedin, Rikard, Henrik CF Bauer, and Peter Wersäll. “Failures after operation for skeletal metastatic lesions of long bones.” Clinical orthopaedics and related research 358 (1999): 128-139.

- Healey, John H., and Holly K. Brown. “Complications of bone metastases.” Cancer 88.S12 (2000): 2940-2951.

- Marco, Rex AW, et al. “Functional and oncological outcome of acetabular reconstruction for the treatment of metastatic disease.” JBJS 82.5 (2000): 642.

- Bickels, Jacob, et al. “Function after resection of humeral metastases: analysis of 59 consecutive patients.” Clinical orthopaedics and related research 437 (2005): 201-208.